My co-founder Jen West and I recently delivered two training workshops to operational-level staff (12 participants in each workshop) from two separate areas within the same organisation. These ‘pilot’ workshops were designed to trial the delivery of a new concept in teamwork which would impact the two organisational groups. The outcomes of these pilot workshops would determine whether or not similar workshops would be rolled out to the remaining 150 staff across these two organisational groups.

So we needed to get two things right: (1) the workshop content and delivery needed to be spot on, and (2) we needed a solid and objective way to measure the workshop outcomes so the organisation could make a call on whether or not they would continue to roll the program out to the other staff.

This raised some interesting issues for us. It made us really think about the intent of the workshops, and how we could objectively assess the workshop outcomes.

In the end, we designed a one page evaluation questionnaire which participants completed at the end of the workshops. This questionnaire included some pointed questions and used a combination of tick boxes (for quantitative analysis) and comments boxes (for qualitative analysis).

We felt the workshops went really well and this was reflected by participants in the evaluation questionnaires. We were happy and so was the client, so all was good.

Some weeks later, we came across a model which would have helped us address some of the challenges we faced in designing an assessment for the workshops. Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy of training evaluation was developed in 1976. We’d never heard of it, so we thought we would share it around.

Whilst the model is designed to assess training effectiveness, we think it can be adapted to also provide a useful framework for developing training strategy or, indeed, any organisational change initiative.

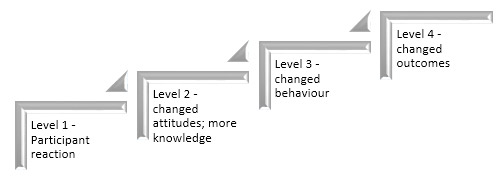

The model is outlined below, and comprises four levels:

Figure 1. Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy of training evaluation

- Level 1 (reactions) assesses participant reactions to the training. In essence this is the equivalent of measuring customer satisfaction.

- Level 2 (learning) assesses attitudinal change and knowledge gained. Did participants acquire knowledge, or did they modify their attitudes or beliefs as a result of attending the training?

- Level 3 (behaviour) assesses whether knowledge learned in training actually transfers to behaviours on the job or a similar simulated environment. Did participant behaviour change when they returned to work after the training?

- Level 4 (organisation) assesses what is (presumably) the ultimate aim of any training program; impact at an organisational level. What were the outcomes at an organisational level as a result of the training – for example, reduction in safety incidents, productivity improvements, etc?

On reflection, our post-workshop evaluation questionnaire addressed levels 1 and 2 of Kirkpatrick’s model – which is probably all that can be achieved immediately after a workshop. So assessing levels 1 and 2 is relatively easy and immediate. But should we have done more?

Assessing level 3 would have been more challenging. This would probably require interviews with participants and work colleagues some weeks after the training, or making independent observations of on-the-job performance. (Note, on-the-job observations are routinely undertaken in the aviation industry via ‘Line Operations Safety Audits’ or LOSA – but that’s another story).

Assessing level 4 outcomes would have been similarly challenging, as organisational level impacts can take some time to manifest and the causal chain between the training and organisational outcome is often loose. In aviation, for example, accident rates have dropped since ‘crew resource management’ training programs were introduced in the 1980s, however, other changes have also been implemented during that period such as improvements in technology, aircraft design, etc. These all impact favourably on aircraft safety and although it is widely accepted that ‘crew resource management’ training has markedly improved aviation safety, a statistically valid assessment of this is not possible due to all the other contributing influences.

Had we known about Kirkpatrick’s model, we could have used this in the strategy development stage, and given some structure to the initial client discussions. (It seemed that the client’s three representatives were not clear or unified on the intended outcomes from these workshops).

Kirkpatrick’s model would have been useful to channel these strategy discussions with the client by asking the following questions:

- Is it realistic to expect these workshops to result in new knowledge and changed attitudes in all or some of the participants (Kirkpatrick’s Levels 1 and 2)? The expected answer would probably be ‘yes’.

- Is it realistic to expect individual participants attending a one-day workshop, to return to their workplaces (with their usual supervisors, processes and workplace cultures) and exhibit behavioural change (Kirkpatrick’s Level 3)? The answer to this would probably be less clear cut; it would be good if this was the case, however, you could argue that a critical mass of people within a particular work area would need to undergo similar training to provide inertia to support individual behavioural change.

- Is it realistic to expect that 24 operational level staff (from a larger group of 170) undertaking a one-day training program would result in improved organisational performance outcomes (Kirkpatrick’s Level 4)? The expected answer would probably be ‘no’.

As W Edwards Deming once remarked “All models are wrong but some can be useful”, and Kirkpatrick’s model would have been useful for us to focus attention on what outcomes the client was realistically hoping to achieve from two pilot programs, and how we could best evaluate this. This post-workshop reflection was a great learning for us, and we thank (the late) Donald Kirkpatrick, former Professor Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin for his simple wisdom.

Graham Miller, co-founder Humans Being At Work